The Weekly Weird #59

Serbian smokeshow, SoKo goes d'oh, Atlas plugged, eye on Shenzen, Ai reads the moo-d and sees in the dark, A Tale of Two Tiers (Part II), civil wha'?

Howdy ho! Here we are again, at the precipice of another dive into the weird and worrying world of dystopian trends!

Serbian Smokeshow: Balkan Insight reports that “Serbian MPs from the ruling majority and opposition brawled on Tuesday inside the National Assembly chamber, where smoke bombs were also set off on the first of this year’s parliament sessions.” In the aftermath of a railway station canopy collapse in the city of Novi Sad in November 2024 that killed 15 people, “large-scale student and citizen protests” have roiled the Balkan country and led to the resignation of Prime Minister Milos Vucevic last month. The tragedy has led to at least 13 people being criminally charged, and has been held up by protesters as a prime example of government corruption.

SoKo Goes D’Oh: A South Korean fighter jet “accidentally dropped multiple bombs on a civilian village in Pocheon, Gyeonggi Province, on Thursday, injuring seven people and damaging several buildings”, according to The Korea Herald. “The South Korean Air Force confirmed that during a live-fire drill conducted as part of the Freedom Shield Exercise 2025…a KF-16 fighter jet mistakenly released eight MK-82 bombs outside the designated firing range near the Seungjin Training Ground in Pocheon.” Reuters subsequently reported that 15 people were injured, and that “[t]he accident was due to a pilot entering incorrect coordinates.” It’s another blow to public trust after the recent abortive attempt by the country’s president to declare martial law.

Atlas Plugged: Noted robotics firm and horror factory Boston Dynamics have dropped a new video going behind the scenes in their lab as they cook up the newest version of their humanoid robot, Atlas. The soothing music and cheerful interview footage almost manage to gloss over the cold reality of the inexorable trudge towards the replacement of humans with computerised automatons.

Eye On Shenzen: TechAltar put up a new video on Shenzen, a southern Chinese city close to Hong Kong that has undergone tremendous modernisation in recent years. The 20-minute video, called China’s city of the future: utopia or dystopia?, is well worth watching and definitely gives a flavour of near-Demolition Man levels of hyper-scrubbed techno-tarianism. Perfectly encapsulating the vibe of the video overall, the presenter describes the new facial recognition ticket gates at a train station as “kinda futuristic, kinda creepy.”

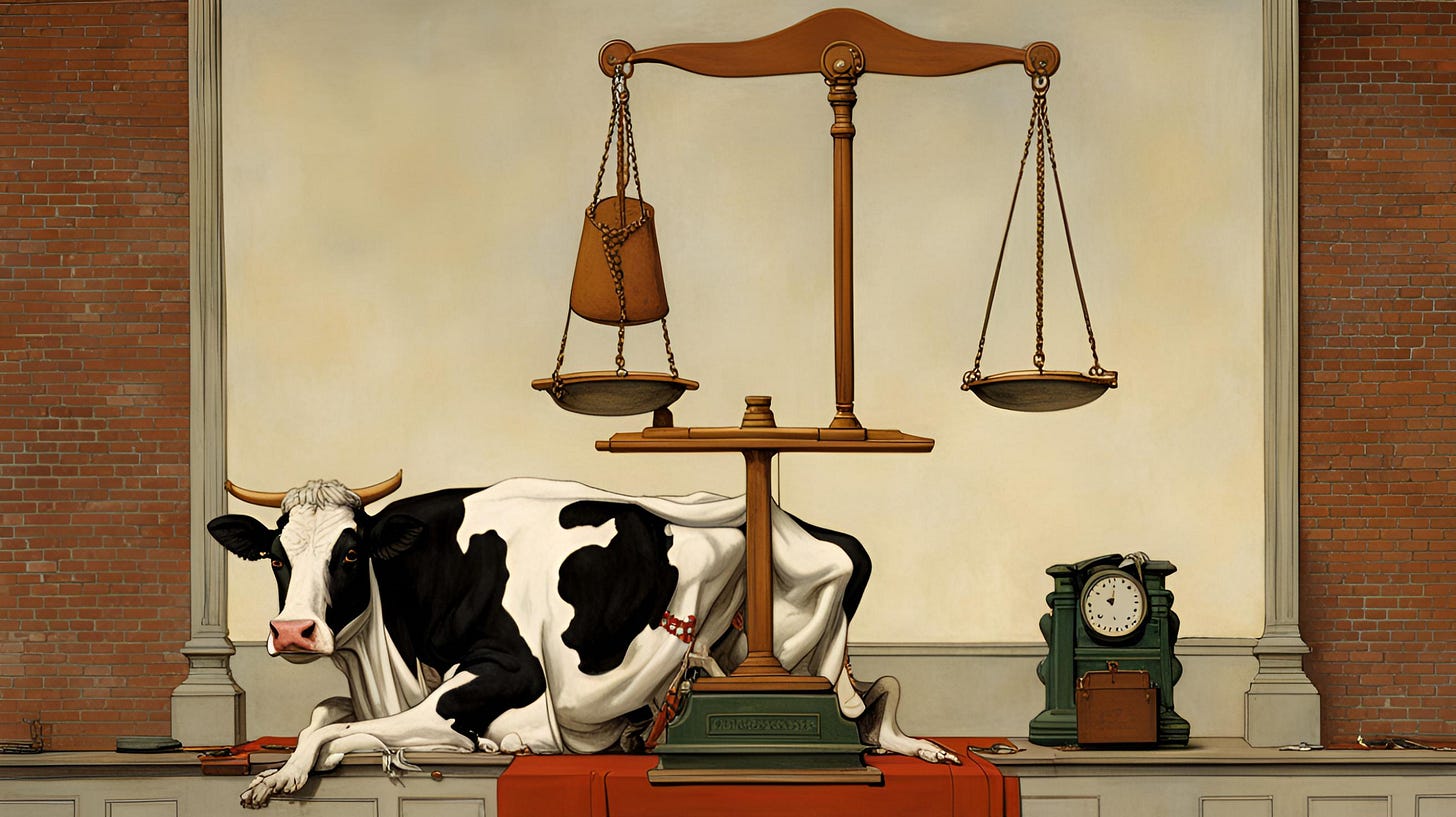

AI Reads The Moo-d And Sees In The Dark: Science Daily reported on two recent advances in the past few weeks. Neuromorphic exposure control (NEC) will improve “machine vision in extreme lighting environments”. “By fusing event streams with physical light metrics, we bypass traditional bottlenecks to deliver lighting-agnostic vision,” declares the study, which claims marked improvements to the way that machines see in blindingly bright and extremely dark situations. Your self-driving car will be 47% better at exiting a tunnel into bright sunlight, but the robot police and Black Mirror-style robot dogs will be better able to spot you in total darkness. Swings and roundabouts. Meanwhile, researchers at the University of Copenhagen claim they have been able to use AI to decode the emotions of seven ungulate species, including cows, pigs, and wild boars. “By analysing the acoustic patterns of their vocalisations, the model achieved an impressive accuracy of 89.49%, marking the first cross-species study to detect emotional valence using AI.” Élodie F. Briefer, an associate professor in the university’s Department of Biology, explained that the breakthrough will “revolutionise animal welfare, livestock management, and conservation, allowing us to monitor animals' emotions in real time.” It is not clear how exactly the researchers were able to confirm the “emotional valence” they detected in order to get a granular percentage figure for accuracy. Did they ask the pigs how they felt after noting what the AI thought? You can read their paper to find out, or check out the following handy graphic illustrating their process:

Gender-Affirming Surgery Outcomes: The Journal of Sexual Medicine, from Oxford University Press, has published a new study that claims to have found that “[g]ender-affirming surgery, while beneficial in affirming gender identity, is associated with increased risk of mental health issues.” The key takeaway of the study is the conclusion that, despite much argument to the contrary from activists, NGOs, and some doctors, “those undergoing surgery were at significantly higher risk for depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and substance use disorders than those without surgery.” Specifically, when compared to a “matched cohort” that had not undergone surgery, “[m]ales with surgery showed a higher prevalence of depression…and anxiety…[f]emales exhibited similar trends, with elevated depression…and anxiety [while] [f]eminizing individuals demonstrated particularly high risk for depression…and substance use disorders.”

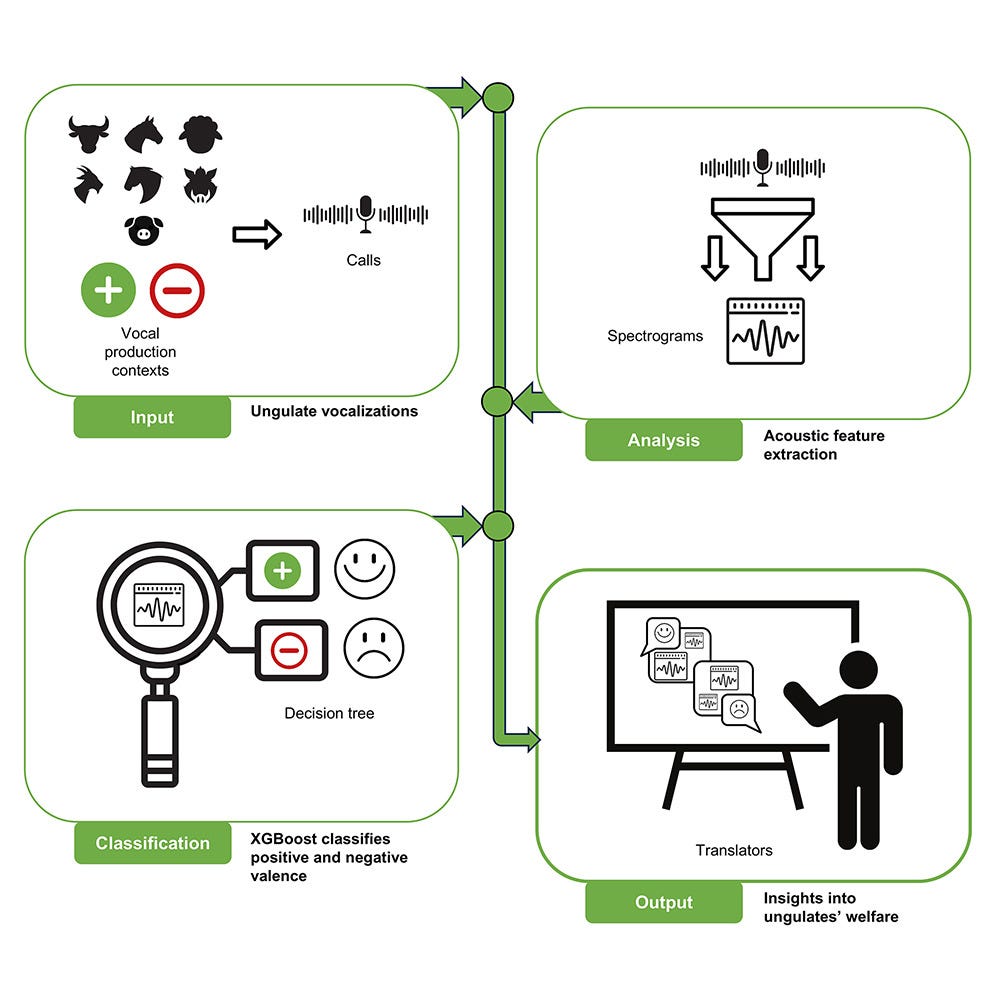

A Tale Of Two Tiers (Part II)

The UK’s Sentencing Council, which issues guidance on how convicted offenders are to be sentenced by British courts, is at the centre of a major row this week, with even government ministers talking down the ‘independent arms-length’ body’s “plans to make the ethnic background of offenders a greater factor in determining whether to jail them”.

The new guidance, set to come into effect from 1 April 2025 (April Fool’s Day for those with a sense of humour), appears to enshrine within the judicial system the principle of differential sentencing depending on the defendant’s immutable characteristics or self-identification.

The focus of the controversy is the Sentencing Council’s new guidance on pre-sentence reports (PSRs), documents that are prepared by a third party to inform a judge’s opinion prior to determining the penalty for a convicted defendant:

The guidance is unequivocal in stating (emphasis in the original) that “the court must request and consider a pre-sentence report (PSR) before forming an opinion of the sentence, unless it considers that it is unnecessary.” As to what does and does not constitute or define necessity, the guidance refers the reader to Section 30 of the Sentencing Code, but here’s the glory of British law in a nutshell: The referenced section of the Sentencing Code says the court “must obtain and consider a pre-sentence report…unless, in the circumstances of the case, it considers that it is unnecessary to obtain a pre-sentence report.” Even better, Paragraph 4 of Section 30 reads:

Where a court does not obtain and consider a pre-sentence report before forming an opinion in relation to which the pre-sentence report requirements apply, no custodial sentence or community sentence is invalidated by the fact that it did not do so.

Pure matryoshka doll magic. So PSRs are obligatory (remember the word “must”?), unless the court doesn’t think it needs one, in which case it doesn’t need it, and even though obtaining and considering the PSR is required by the guidance and the Sentencing Code, not obtaining and considering a PSR has no effect on the validity of the sentence. Got it?

Here’s how it works:

A requirement is imposed in vague language.

Additional language is included that makes it clear that the requirement is not required.

There is no penalty for ignoring the requirement, even though the guidance states clearly that it is obligatory.

Therefore, anyone can argue that there is no requirement, while in practice the requirement becomes a part of the system, which at any time can ignore it at its own convenience while claiming it doesn’t exist.

Remember these steps as you watch the following TalkTV segment on the new guidance. At 4:51 you’ll find a brief exchange with a lawyer named Francesca Cociani who argues that the discriminatory implication of the guidance “doesn’t create a two-tier justice system [but] quite the opposite” and then goes on to claim that the guidance isn’t mandatory anyway, which is technically true according to how it is written while being demonstrably irrelevant relative to how the system actually functions and adopts guidance.

Cociani suggests that the potentially discriminatory guidance is required to redress perceived systemic racism and bias in courtroom outcomes and is a useful step towards that aim.

This is the Ibram X. Kendi approach to justice:

“The only remedy to past discrimination is present discrimination. The only remedy to present discrimination is future discrimination.”

That quote comes from a passage in which Kendi also quotes Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun writing in 1978 that “in order to treat some persons equally, we must treat them differently.”

Something about that formulation, while understandable in the specific context of a recently desegregated United States, sounds eerily familiar…

As Pamela Paul wrote in an op-ed for the New York Times on October 5, 2023: “Kendi’s strident, simplistic formula [is] that racism is the cause of all racial disparities and that anyone who disagrees is a racist.”

As to whether such a concept is applicable, let alone useful, outside of the national historical and social context from which it sprang, some people might argue that Britain in 2025 is not the same as the United States was in 1978, or even in 2019, when Kendi published his book How To Be An Anti-Racist, but let’s leave that aside for now.

The disparities in question appear to be the proportion of prosecutions for indictable offences and the lengths of custodial sentences.

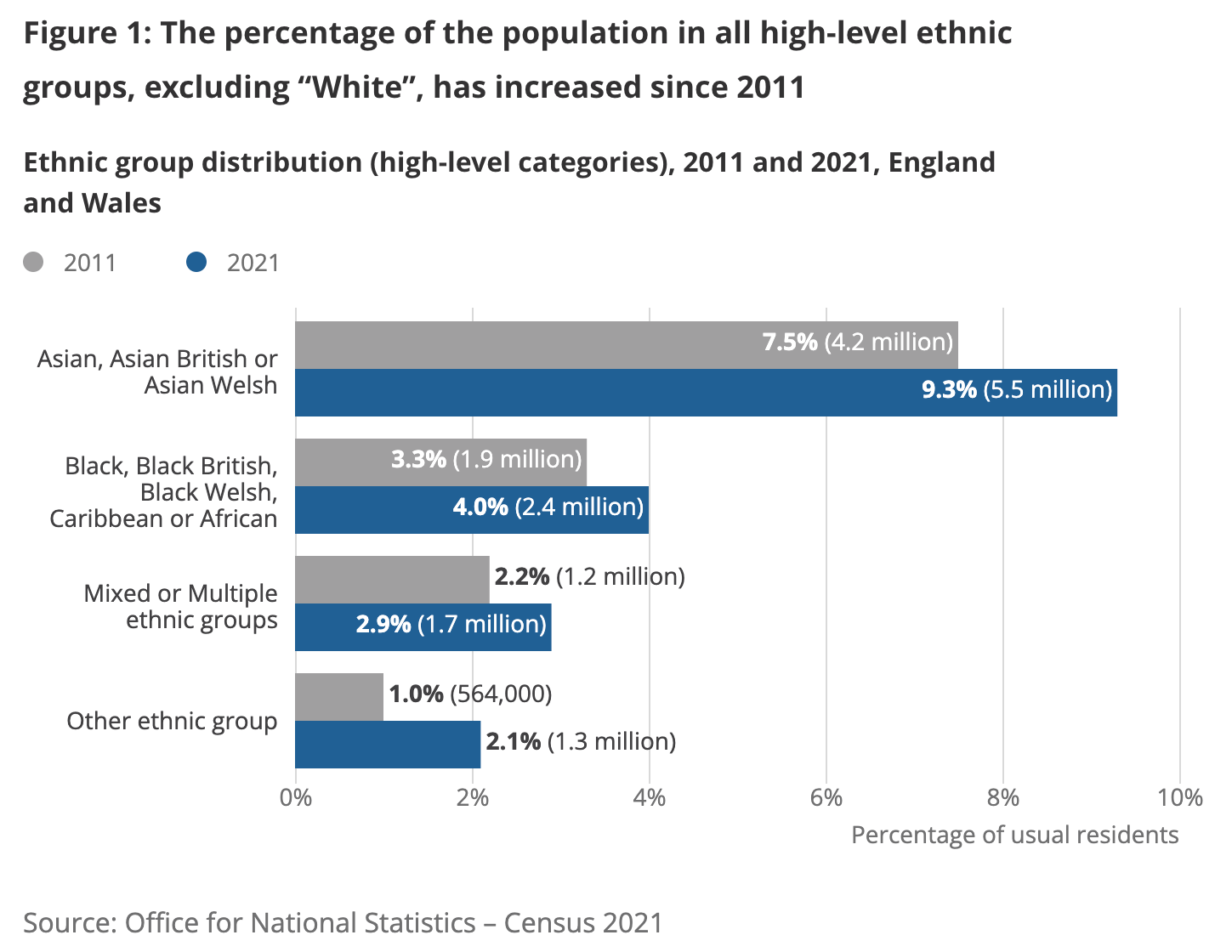

The ethnicity of the population of England and Wales, as measured by the 2011 and 2021 censuses, was 81.7% “white” in 2021 (down from 86% in 2011), with the other “high-level ethnic groups” as follows:

The percentages don’t match exactly, and when the lengths of custodial sentences are factored in (especially when categorised by offence), there are clear but inconsistent disparities.

For example:

86% of prosecuted women are white against 81.7% of the broader population.

7% of male prosecutions are Asian against 9.3% of the broader population.

Asians get sentences for criminal damage and arson that are, on average, 13 months longer than white or black convicts.

Black convicts are sentenced to an average of 39 months for “violence against the person” against 21 months for white convicts or 30 months for Asians.

Of course, the statistics don’t seem to include anything granular as to the nature of the crimes, the outcome for the victim, the motive etc., all of which would affect how the defendant is treated by the judge at their trial. None of what follows is claiming there aren’t disparities in legal outcomes, or that there is no possibility that bias can play a role in how cases are prosecuted or how judges determine sentences.

That said, the sleight of hand by which equality of outcome is swapped in for equal treatment under the law is deft. If people of certain backgrounds are disproportionately represented in courts and prisons as defendants and convicts, the application of Kendi’s “formula” presupposes that racism, i.e. discrimination, is the cause. Therefore, the formula dictates that fewer people from the allegedly affected group should end up on trial or be sent to prison, since they are only there due to structural and systemic bias, an assertion that is as unprovable as it is unfalsifiable, since presenting an alternative to racism as an explanation for unequal outcomes would be, according to Kendi, racist.

Back to Pamela Paul for more on Kendi’s framework (emphasis in the original):

In “Stamped From the Beginning,” Kendi asserted that racist ideas are used to obscure the fact that racist policies create racial disparities and that to find fault with Black people in any way for those disparities is racist. People who “subscribed to assimilationist thinking that has also served up racist beliefs about Black inferiority,” no matter how well meaning and progressive, were themselves racist. In Kendi’s revisionist history, figures who were previously hailed for their contribution to civil rights were repainted as racist if they did not attribute Black inequality solely to racism. Kendi accused W.E.B. Du Bois and Barack Obama of racism for entertaining the idea that Black behavior and attitudes could sometimes cause or exacerbate certain disparities, although he noted that Du Bois went on to take what he considered a more antiracist position.

In 2019, Kendi took the ideas further, pivoting to contemporary policy with “How to Be an Antiracist.” In this book he made clear that to explore reasons other than racism for racial inequities, whether economic, social or cultural, is to promote anti-Black policies.

“The only remedy to racist discrimination is antiracist discrimination,” Kendi wrote, in words that would be softened in a future edition after they became the subject of criticism. “The only remedy to past discrimination is present discrimination. The only remedy to present discrimination is future discrimination.” In other words, two wrongs do make a right.

How does this theory make the jump across the Atlantic Ocean to sentencing guidelines in Great Britain?

As Paul points out, “Kendi asserts that whether a policy is racist or antiracist is determined not by intent but by outcome.”

If a disproportionate number of people of a particular ethnicity, e.g. a higher percentage than measured among the general population in a census, are being incarcerated, that proves the judicial system is biased regardless of other factors. Institutionalising this premise in the UK is explicitly aimed at changing outcomes and furthering the entrenchment and acceptance of the framework.

More from Paul:

Among the book’s central tenets is that everyone must choose between his approach, which he called “antiracism,” and racism itself. It would no longer be enough for an individual or organization to simply be “not racist,” which Kendi called a “mask for racism” — they must instead be actively “antiracist,” applying a strict lens of racism to their every thought and action, and in fields wholly unrelated to race, in order to escape deliberate or inadvertent racist thinking and behavior.

The irony is that reading systemic racism into every interaction and outcome in society contributes to and exacerbates “hostile attribution bias”, which in turn deepens the conviction that society is hopelessly prejudiced and increases the demand for measures to counteract the perceived discrimination, even where none exists.

The Network Contagion Research Institute published a study in late 2024 called INSTRUCTING ANIMOSITY: How DEI Pedagogy Produces the Hostile Attribution Bias that dealt with this issue in detail. Unfortunately, the Sentencing Council in Britain don’t seem to have read it.

In one ‘scenario’ in the study, participants were divided into groups and given a text to read. One group was given an “anti-racist” text containing excerpts from the writings of Kendi and Robin diAngelo, while the other group were given a “neutral” account of corn production in the United States. After reading, both groups were then given a description of the same scenario: “A student applied to an elite East Coast university in Fall 2024. During the application process, he was interviewed by an admissions officer. Ultimately, the student’s application was rejected.”

What followed is fascinating, if unsurprising (emphasis mine):

Participants were then asked to evaluate the scenario with questions designed to probe the extent to which they perceived racism in the interaction. This scenario intentionally avoids any mention of either the student’s or admission officer’s race or ethnicity and provides no evidence of racism. Thus, if they perceive racism in the interaction, they are introducing something that is objectively absent.

[…]

[P]articipants who read the Ibram X. Kendi/Robin DiAngelo essay developed a hostile attribution bias. They perceived the admissions officer as significantly more prejudiced than did those who read the neutral corn essay. Specifically, participants exposed to the anti-racist rhetoric perceived more discrimination from the admissions officer (~21%), despite the complete absence of evidence of discrimination. They believed the admissions officer was more unfair to the applicant (~12%), had caused more harm to the applicant (~26%), and had committed more microaggressions (~35%). The strength of these notable results motivated NCRI to test for replicability with an experiment on a national sample (n=1086 recruited via Amazon Prime Panels) of college/university students to ensure these findings were not an aberration of student attitudes on Rutgers campus. These findings showed similar, statistically significant effects.

Similar scenarios involving Islamophobia and the caste system produced equally clear results.

Regarding Islamophobia:

These results suggest that anti-Islamophobia training inspired by ISPU [Institute for Social Policy and Understanding] materials may cause individuals to assume unfair treatment of Muslim people, even when no evidence of bias or unfairness is present. This effect highlights a broader issue: DEI narratives that focus heavily on victimization and systemic oppression can foster unwarranted distrust and suspicions of institutions and alter subjective assessments of events. In the effort to improve sensitivity to genuine injustices against people from designated identities, such trainings may instead create a hostile attribution bias. This could, in turn, undermine trust in institutions, even in the absence of bias or unfair treatment.

For the caste system scenario, participants were either given the ‘control’ text or a text on caste system discrimination prepared by Equality Labs. After reading, they were presented with a scenario: “Raj Kumar applied to an elite East Coast university in Fall 2022. During the application process, he was interviewed by an admissions officer, Anand Prakash. Ultimately, Raj’s application was rejected.”

Participants were then asked to evaluate the scenario with questions designed to probe the extent to which they perceived casteism in the interaction.

Results: Analysis revealed that exposure to the Equality Labs intervention led to significantly higher perception of microaggressions, perceived harm, and assumptions of bias during the interview process (increases of 32.5%, 15.6%, and 11%, respectively) compared to the control condition.

Whether or not you accept the premise that disproportionate outcomes presuppose inherent systemic bias, the argument that institutionalising differential treatment of certain groups of people is a balancing mechanism and can’t be seen as discriminatory, or the axiom that only discrimination can fix discrimination, even while the adherent to that axiom is arguing that the discrimination being implemented to fix perceived prior discrimination isn’t actually discrimination at all, it takes a serious empretzelment of mind to claim this doesn’t create the conditions and give tacit approval for a two-tier system of justice.

Add in the body of research that shows people become more suspicious of one another, less trusting of institutions, and less patient with and sympathetic towards the actions of others once they are exposed to this framework for categorising and judging social interactions and outcomes, and it’s even harder to swallow.

Even the Labour government’s justice secretary Shabana Mahmood has come out against the new guidance: “As someone who is from an ethnic minority background myself, I do not stand for any differential treatment before the law, for anyone of any kind. There will never be a two-tier sentencing approach under my watch.”

Are we really helping society by introducing this kind of ideology into the structure of the state? Or will it prove counterproductive, corrosive, and possibly even dangerous?

Well, funny story…

Civil Wha’?

The journalist and author Louise Perry had Professor David Betz, Professor of War in the Modern World at King's College London, on her podcast for a conversation about Britain.

The professor was not optimistic. In his view, “the main threat to the security and prosperity of the West generally and the UK specifically now is civil war, not external war,” and he says “British society is fundamentally explosively configured.”

“Legitimacy is a kind of magic that makes a government work,” he said, before going on to accuse the British government of “following some kind of game plan for destroying legitimacy.” He thinks the situation in Britain is “too far gone” and that violent unrest or even civil war could be expected within the next five years.

With so many experts, historians, and advisers who are well-educated about the past and the situations in other countries, and with an intelligence establishment practiced in the study (and execution) of destabilisation of foreign regimes, somehow the British government is still “leading us to civil conflict according to our own well-established ideas about what causes civil conflict.” It would be ironic if it wasn’t so worrying.

For Betz, a key driver is the perceived failure of governments to uphold the social contract, leading to a rupture between the people and the state. He envisions a potential civil conflict beginning with elements of a “dirty war” (i.e. assassinations, kidnappings, and political violence), escalating into a broader conflict with a significant rural-versus-urban dimension.

Potential attacks on urban infrastructure (gas, electricity, transportation) by anti-status quo elements could lead to systemic failure and population displacement within cities. He uses the term “feral city” to describe ungovernable, chaotic cities with failing infrastructure. He adds that governments are being fooled by technology companies into believing that they can make up for their lack of legitimacy with tech, while he feels it’s likely that people will eventually begin destroying the surveillance infrastructure continually encroaching on their privacy, autonomy, and anonymity.

In some cases, that’s already happening. Check out the “unpaid voluntary work” of the Blade Runners in London…

If you really want a hoot, you might enjoy The Death Of Grass by John Christopher, one of the more harrowing post-apocalyptic novels set in Britain.

That’s it for this week’s Weird, everyone. I hope you enjoyed it.

Outro music is, of course, Civil War by Guns ‘n’ Roses. What else could it be this week?

What’s so civil about war anyway?

Stay sane, friends.

If I have said this before, my apologies, but it simply bears repeating…The common folk of the UK are in terrible dire straits because the governments have fully and completely embraced the dystopian narratives. Civil war seems plausible but how do citizens fight when they have been disarmed?