Britain's Pre-Crime Project

Documents obtained by Statewatch reveal a "homicide prediction project" straight out of a Philip K. Dick story

The United Kingdom, that sceptr’d isle, is taking yet another step towards a Dickian (Dickish?) future. It’s as if the Ministry of Justice has been combing through Dick’s story The Minority Report for policy ideas.

According to documents obtained by Statewatch through freedom of information requests:

The Ministry of Justice is developing a system that aims to ‘predict’ who will commit murder, as part of a “data science” project using sensitive personal data on hundreds of thousands of people.

The Guardian ran with the story:

The scheme was originally called the “homicide prediction project”, but its name has been changed to “sharing data to improve risk assessment”. The Ministry of Justice hopes the project will help boost public safety but campaigners have called it “chilling and dystopian”.

Statewatch explains the project further:

The Homicide Prediction Project uses police and government data to profile people with the aim of ‘predicting’ who is “at risk” of committing murder in future. It is a collaboration between the Ministry of Justice (MoJ), the Home Office, Greater Manchester Police (GMP) and the Metropolitan Police in London.

For anyone keeping track:

That’s the same Greater Manchester Police responsible for “multiple failed investigations…and an apparent indifference to the safety of the young girls identified as potential victims”, according to an independent review covering that police force’s work (or lack thereof) on ‘grooming gangs’ and child sexual abuse between 2004 and 2013.

The Metropolitan Police, as recently as 2023, were subjected to a year-long review by Baroness Casey that, as per the BBC, found “systemic failures”, including one incident in which “rape cases were dropped because a freezer containing key evidence broke.” Why was there a review? It was ordered “after the [2021] abduction, rape and murder of Sarah Everard by serving police officer Wayne Couzens”. Also in 2023, David Carrick “pleaded guilty to 49 charges, including 24 counts of rape” and was “sentenced to 36 life terms” or, as Britain’s penal system would have it, “a minimum term of 32 years in jail”. His crimes “all took place while he was a serving officer” in the Metropolitan Police. This 2024 article from the Guardian on police misconduct is also illuminating.

The Ministry of Justice was caught, in 2024, “hiding from Parliament that it had awarded two new electronic tagging contracts worth more than £500 million to two companies that had been investigated by the Serious Fraud Office, fined £57.7 million, and had to repay £70.5 million to the ministry for fraudulent claims,” according to the Byline Times. Yeah, the Ministry of Justice awarded contracts to companies that had committed “quite deliberate fraud against the Ministry of Justice” in the past, and then concealed it from Parliament. That doesn’t even open the can of writhing worms that is the Post Office scandal.

As for the Home Office, we’re going to need more bullet points, or you can check out this 2022 list of eight reasons why they “can’t be trusted with more power”:

This week, a new scandal broke that “[a]t least £22,000 was spent by the Home Office on hiring lawyers in a failed attempt to prevent the release of a hard-hitting internal report that found that the roots of the Windrush scandal lay in 30 years of racist immigration legislation”.

In February, the Home Office was “accused of collecting data on "hundreds of thousands of unsuspecting British citizens" while conducting financial checks on migrants.” Details of people who had “previously lived or worked in the same address or postcode area” as the migrants in question were caught in the data dragnet, even though “some of the people listed had left as far back as 1986”.

In January, the Telegraph reported on a “leaked dossier” from the Home Office in which they recommended that “[p]olice should record more non-crime hate incidents”. According to Sky News at the time, the leaked documents also “suggested the UK should be focusing on behaviours and activities such as spreading conspiracy theories, misogyny, influencing racism and involvement in "an online subculture called the manosphere".” That certainly makes the government’s rush to gush over the Netflix show Adolescence seem slightly less spontaneous, doesn’t it?

In November 2024 it was reported that the Home Office “may have to refund tens of millions of pounds to people who were ‘unlawfully’ charged fees for checks in their visa applications”, an oversight that endured for years “due to a mistake dating back to at least 2008”. The government at the time rushed “to rectify the blunder with new legislation”, a plan that included the suggestion of “a "restitution scheme" for people unlawfully charged the fees, or passing a new law to make them retrospectively legal.”

In 2024, a Home Office case worker used “sensitive Home Office records…as part of [an] attempted scam”, the object of which was “to sell UK residency to an asylum seeker living in Northern Ireland”.

In March 2024, the Guardian reported on a “database fiasco” revealed by leaked documents, in which “[m]ajor flaws in a huge Home Office immigration database have resulted in more than 76,000 people being listed with incorrect names, photographs or immigration status.” This story is of particular interest in the context of the Home Office’s involvement in a pre-crime initiative, since according to the Guardian they were “relatively silent about the database failures, referring vaguely to them as "IT issues"”. How bad were the “IT issues” in this incident?

“The problem, which involves “merged identities”, where two or more people have biographical and biometric details linked incorrectly, is leaving people unable to prove their rights to work, rent housing or access free NHS treatment.”

In January 2023 the European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE) reported that the Home Office had been “accused of "dereliction of duty" after 200 child asylum seekers went missing from its hotels”.

All of this is to say that the four organs of the state involved in the “Homicide Prediction Project” have deficient track records when it comes to upholding their obligations to the public, performing their duties in a transparent manner, proactively preventing abuse of position and power by their employees, managing investigations in which crimes already happened, and, most troublingly, proving that they can handle complex technology and “IT issues” in a way that doesn’t result in collecting too much data or data on the wrong people, merging or linking identities incorrectly, or sending hundreds of innocent people to prison.

Statewatch’s article expanded further on the scale of the project:

The so-called predictive tool uses data from the MoJ, the Police National Computer and GMP, to attempt to make these ‘predictions’.

The Data Sharing Agreement between the MoJ and GMP for the Homicide Prediction Project notes that data on between 100,000 and 500,000 people was shared by the force to develop the tool.

The MoJ says in the documents that the project is intended to “[e]xplore the power of MOJ datasets in relation to assessment of homicide risk.” The MoJ Data Science team then “develops models” seeking “the powerful predictors in the data for homicide risk”. The documents refer to the “future operationalisation” of the system.

The GMP data used by the MoJ to develop the tool includes information on hundreds of thousands of suspects, victims, witnesses, missing people, and people for whom there are safeguarding concerns.

The data also includes information on people in vulnerable situations, with the MoJ stating that “health markers” data was “expected to have significant predictive power”. This includes data on people’s mental health, addiction, self-harm, suicide, vulnerability, and disability.

Let’s leave aside the ethical swamp of using data on people at their most confused, emotional, and vulnerable, often gathered in a setting in which they as patients understandably expect privacy and anonymity, as inputs in a predictive algorithm that could mark them as a potential criminal before they’ve done anything illegal. Let’s put a pin in that, the grossness of it speaks for itself.

According to the Office of National Statistics, homicides are down 3% year-on-year, with 570 being recorded for 2024 nationwide. Since a spike in 2003 (attributed to the serial killer Harold Shipman), incidents of homicide in Britain are down 47% over the past 22 years.

A study of homicide case clearance in England and Wales published in February 2025 gives some helpful context, including that “almost 60% of the British homicide cases…were solved in the first 48 hours.”

Compared with some countries in the Americas or Africa, homicide is a relatively low-volume offense in England and Wales with a rate of 1.15 per 100,000 population in 2021, compared to 42.40 in South Africa, 21.26 in Brazil and 6.81 in the United States of America, although the rate in Canada is only slightly higher at 2.09.

Countries with homicide rates even lower than England and Wales include: “Switzerland (0.48), Norway (0.55) and Italy (0.55)”, while “the rate for Australia and New Zealand is 0.83, and as low as 0.12 in Singapore and 0.23 in Japan.”

So what data could be useful to take a view on how a predictive algorithm might help flag potential murderers?

Interestingly, in England and Wales, while young people aged 20 to 29 face the highest risk of victimization compared to other 10-year age groupings, children aged under one have the highest homicide rate per million population in England and Wales.

The majority of homicides recorded in England and Wales between 2008 and 2019 were committed by someone known to the victim. Consequently, stranger homicides are relatively rare in England and Wales with a rate of 0.14 per 100,000 population in 2021, compared to a rate of 1.28 in the United States.

If the age group in England and Wales most at risk of being murdered is children under the age of one, and the majority of murderers are “someone known to the victim”, are new parents going to be flagged by a predictive system?

If, in England and Wales, murder is, if not a low-probability event then at least relatively rare compared to countries of similar population size or economic output, what exactly is the problem that a complex computerised prediction system prone to overreach, abuse, and bias going to solve? Could it possibly do more good than harm?

Sofia Lyall of Statewatch said about the project:

Time and again, research shows that algorithmic systems for ‘predicting’ crime are inherently flawed. Yet the government is pushing ahead with AI systems that will profile people as criminals before they’ve done anything.

[…]

Building an automated tool to profile people as violent criminals is deeply wrong, and using such sensitive data on mental health, addiction and disability is highly intrusive and alarming.

To add weight to the question of why exactly this type of technology is being considered at all, it’s nothing new. Predictive policing has been used elsewhere for long enough to have a track record.

In one example from 2013, Robert McDaniel of Chicago, a man with no violent history, was put on a “heat list” by the city’s predictive policing algorithm as a potential “party to violence”, although the system “couldn’t determine which side of the gun he would be on.”

As reported in The Verge in 2021:

McDaniel was both a potential victim and a potential perpetrator, and the visitors on his porch treated him as such. A social worker told him that he could help him if he was interested in finding assistance to secure a job, for example, or mental health services. And police were there, too, with a warning: from here on out, the Chicago Police Department would be watching him. The algorithm indicated Robert McDaniel was more likely than 99.9 percent of Chicago’s population to either be shot or to have a shooting connected to him. That made him dangerous, and top brass at the Chicago PD knew it. So McDaniel had better be on his best behavior.

The idea that a series of calculations could predict that he would soon shoot someone, or be shot, seemed outlandish. At the time, McDaniel didn’t know how to take the news.

But the visit set a series of gears in motion. This Kafka-esque policing nightmare — a circumstance in which police identified a man to be surveilled based on a purely theoretical danger — would seem to cause the thing it predicted, in a deranged feat of self-fulfilling prophecy.

The nature of the neighbourhood that McDaniel lived in meant that, by visiting him but not as a person of interest in a crime, the police had already marked him.

McDaniel’s neighbors saw the cohort of officials arrive. They saw police walk to his porch, and they noticed that, when they departed, McDaniel didn’t leave along with them in handcuffs.

His family members and people in the neighborhood asked about the visit. Had McDaniel come to some sort of agreement with the police?

“They wanna know why all these muthafuckin’ cops are here talkin’ with me,” McDaniel says. “And you know what? So do I.”

As the Verge’s reporter Matt Stroud points out, the very fact of ending up on the list can be seen by the police as an indication of, if not guilt, then ‘up-to-no-good-ness’.

A commander in the police force eventually told me, “If you end up on that list, there’s a reason you’re there,” implying that people on the list are criminals rather than “parties to violence.”

McDaniel describes how being flagged by the system made him “a target of constant surveillance”:

Police started hanging around the bodega where he worked, looking for opportunities to go after him, often questioning his managers about his activities and whereabouts.

Everywhere he looked, it seemed, there was a police officer waiting for him, ready to search, to seize.

Besides the impact at his job, and a marijuana possession charge, being watched and in regular contact with the police meant that “a lot of his friends and neighbors didn’t trust him”.

McDaniel wasn’t snitching. He wasn’t even being asked to do so in the first place; if the cohort who showed up on his front door was to be believed, they were merely asking him to accept help and keep out of trouble. That’s not what it looked like to anyone in the neighborhood, McDaniel says, as cops seemed to follow him wherever he went.

McDaniel found himself in a kind of worst-case scenario: police were distrustful of him because of the heat list, while his neighbors and friends were distrustful of him because they assumed he was cooperating with law enforcement — no amount of assurances would convince them he wasn’t.

The distrust even led to “a group of men” approaching him in the street to ask whether or not he was a “snitch”.

Take a step back and try to imagine the complexity of what McDaniel was trying to explain in that moment: the reason for cops showing up at his door was a stuff-of-science-fiction computer algorithm that had identified McDaniel, based on a collection of data sources that no civilian could gain access to, as a shooter or a victim of a shooting in some future circumstance that might or might not play out.

One could imagine that some audiences hearing this explanation might think McDaniel was out of his mind — a conspiracy theorist raving about the vast surveillance state.

Days later, he was ambushed coming out of a friend’s house and shot in the knee.

At the hospital after he was shot, McDaniel recalls speaking with someone connected to the shooter. Incredulous, he asks, “What the fuck y’all just shoot me for?”

The response, according to McDaniel: “A lotta muthafuckas don’t believe your story.”

Justifiably, McDaniel’s view of the situation is that the predictive system “caused the harm its creators hoped to avoid: it predicted a shooting that wouldn’t have happened if it hadn’t predicted the shooting.”

It brings to mind the scene in the film The Matrix, where the Oracle tells Neo not to worry about the vase.

“Would you still have broken it if I hadn’t said anything?”

Several years later, in 2020, McDaniel was ambushed a second time, in an alleyway.

Two shooters in black, an attempted hit. A surveillance video from that night shows darkened figures walking through an alley, bursts of gunfire. A figure — McDaniel — falls into a brick wall, then slides down to the ground.

“They did it again,” McDaniel tells me.

McDaniel says he knows who did it, but he won’t go to the police. He says he’s the target of violence because people in his neighborhood believe he’s a snitch. But McDaniel refuses to report the shooting to police because he says he’s not a snitch — and never would be.

The irony here is breathtaking and entirely foreseeable. The heat list may have been designed to reduce violence, but for McDaniel, he says it brought violence directly to him. It got him all the negative ramifications of being an informant — a snitch — with none of the benefits.

The last words in the article go to McDaniel, speaking about the system that put him on a list in the first place.

“I can’t trust them,” he says.

Neither can we.

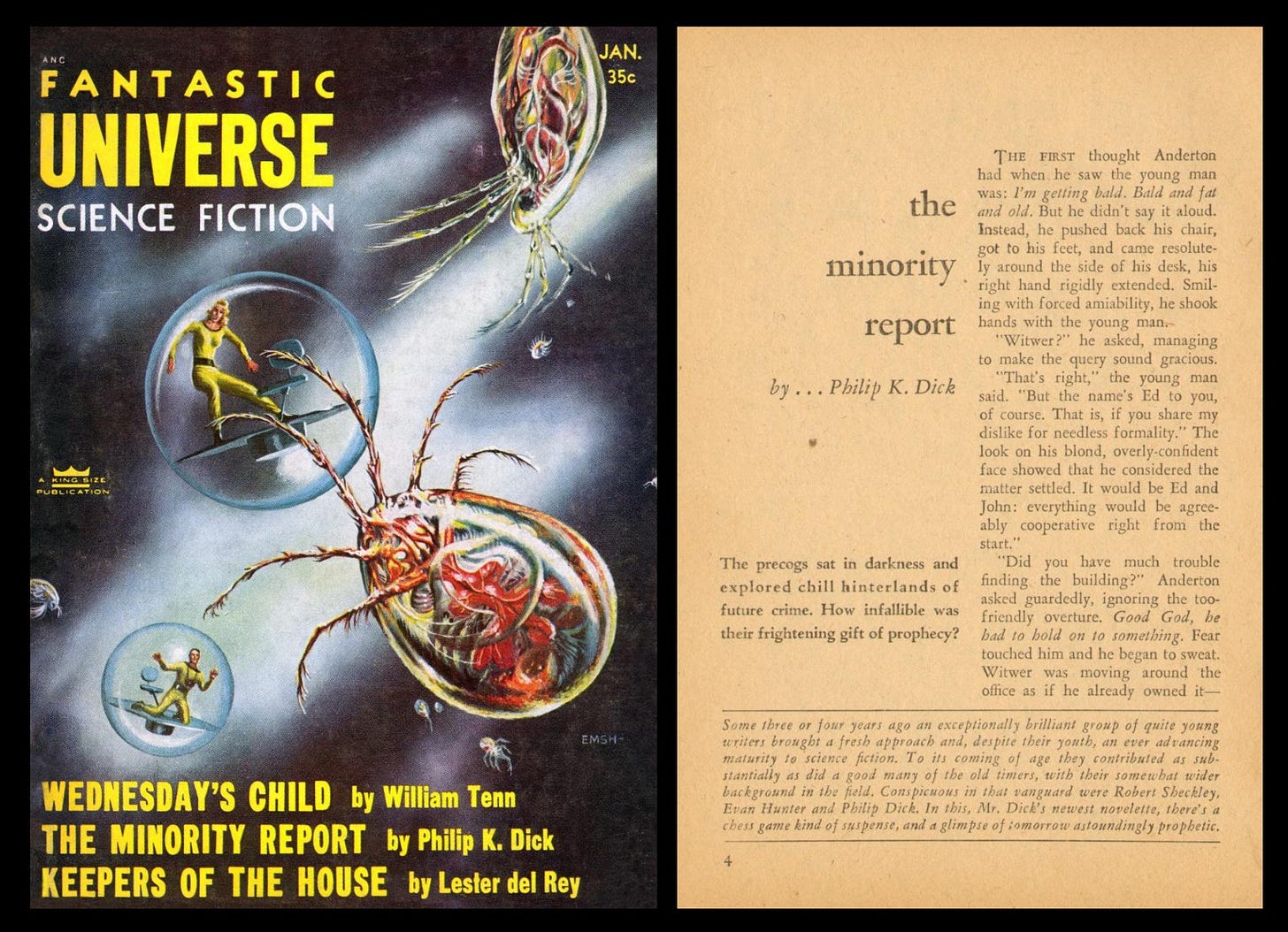

Returning to Philip K. Dick’s story The Minority Report, in which three ‘precogs’ feed their hallucinations into computers to generate reports on future crimes, here’s what the acting commissioner in the story, Witwer, says about “the theory of multiple-futures”:

If only one time-path existed, precognitive information would be of no importance, since no possibility would exist, in possessing this information, of altering the future.

If the future is set, trying to prevent a future event would be senseless. To believe future events can be prevented is to believe that the future isn’t yet written. Therefore, to buy into the efficacy of a pre-crime project is to accept that the same speculative future certain enough to base investigations or even arrests on is also changeable enough to permit fruitful intervention.

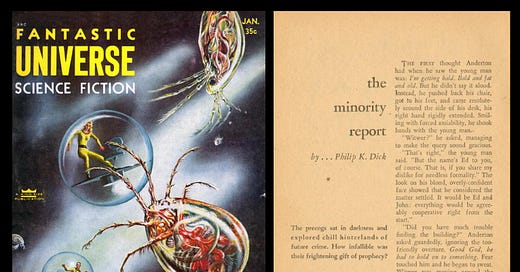

This kind of paradox may be easier to explore in science fiction or philosophy than in public policy, but the logic still applies when examining a government initiative that could have sprung from the pages of a 1950s magazine like Fantastic Universe.

In Philip K. Dick’s words (emphasis in the original):

[T]here can be no valid knowledge about the future. As soon as precognitive information is obtained, it cancels itself out. The assertion that this man will commit a future crime is paradoxical. The very act of possessing this data renders it spurious. In every case, without exception, the report of the three police precogs has invalidated their own data. If no arrests had been made, there would still have been no crimes committed.1

Thankfully, it’s not yet assured that this project will become part of the daily law enforcement toolkit in Britain.

Or is it?

In the story, General Kaplan says this right before Anderton kills him. By committing the crime the precogs accused him of, Anderton is, in a certain way, proving Kaplan wrong. I’m setting aside the context of that moment in the story by using the speech differently here because it’s well-written and makes a good point, but I acknowledge the irony.

Big brother’s big brother is now watching you